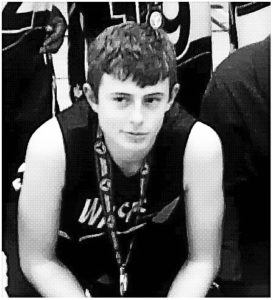

Alex Corrance

Alex Corrance

Alex was an elite athlete. He was a defenseman for the Mississauga Rebels Midget AAA team and also worked out four to six times a week, “Alex just lived for hockey,” remembers his father, Alan. “If it wasn’t ice hockey in the winter, it was roller hockey in the summer, or ball hockey. That was his life and he just loved it all the time, out there hanging with the guys and having a good time.” At 6’2” 190 lb, the 17-year-old was certainly not someone you’d ever suspect of having a fatal heart condition.

The day after Christmas in 2006, Alex and his Dad, drove to a hockey tournament. “He was fine. He was excited about playing, joking around with his teammates right before the game.” Just 10 minutes into the first period the game was stopped. Alan was watching up in the stands when he realized that a player was down. As manager of his son’s hockey team, Alan rushed down to the ice to see who it was. “I was checking out all the players and realized that it was my son. This was really unusual because in all the years Alex played he was rarely injured.”

But Alex hadn’t been hit. According to eyewitnesses, he had just collapsed onto the ice. Both of the team trainers immediately performed CPR and used an Automated External Defibrillator (AED) available at the arena. Off-duty firefighters and nurses assisted until Paramedics arrived and tried to revive Alex while he was rushed to emergency. Hospital staff continued to try and resuscitate Alex but were not able to revive him. “The ER doctor called me into the room to say goodbye to him,” says Alan.

A coroner’s report a few days later identified the cause of Alex’s death: an inherited heart condition known as Arrythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy (ARVC). This is a disease of the heart muscle in which fatty scar tissue replaces the muscle cells of the right ventricle, causing abnormal heart rhythms. Alan, along with Alex’s mother Debbie, were stunned. How could the heart of their extremely fit son simply stop working? “We kept wondering why Alex could have had a bad heart. Turns out, elite training can make the condition worse.”

Dr. Andrew Krahn, a specialist in heart rhythm disorders at the London Health Sciences Centre, explains: “In ARVC, intense exercise causes the heart cells to pull apart because the ‘Velcro’ that holds them together is weak, causing scarring that builds up more rapidly than with moderate forms of exercise. Alex was a super hockey player and his extensive conditioning made his heart vulnerable to cardiac arrest.”

ARVC is difficult to diagnose. Although there are some subtle symptoms, more than 50% of those with the condition exhibit no signs – just like Alex. The symptoms include fainting for unusual reasons – without warning or during physical activity. Sadly, sudden death was the only symptom Alex ever had. And because ARVC runs in families, parents should think back to stories of relatives who died suddenly for no apparent reason at a young age.

In the Corrance’s family, Debbie’s grandmother had passed away unexpectedly in her 30s of unknown causes. In fact, when Dr. Krahn conducted tests on both Alan and Debbie, ARVC was found in her genes.

If caught early, teens with ARVC can manage with medication and participate in moderate activities such as biking and playing baseball. In some cases, a defibrillator may need to be implanted to monitor and treat the heart. Dr. Krahn advises that if your child has had unusual fainting spells and you have had relatives that have died young, you should get the whole family checked out. The first line of testing may include a detailed history, physical examination and performing an electrocardiogram (ECG).

Alan and Debbie hope advances are made not only in the treatment of those with degenerative heart conditions, but also in the detection. “It means a lot to us in getting the awareness out, and, hopefully, medical research will find some way of detecting and improving the treatment,” he said. “Detecting is the important thing.”

The Corrances have kept Alex’s memory alive by hosting an annual 3-on-3 Ball Hockey Tournament. Money raised will be used to support education and awareness of sudden cardiac death in young adults and assist medical research. They also distribute information to parents of active kids about ARVC.

Their advice: “Don’t assume that your athletic child has a healthy heart.”

for the last time. Her heart suddenly stopped beating. There was no witness, no one to perform CPR, no AED. She was found dead by her uncle the next morning when she didn’t get up as planned to accompany her cousin to a special rock-climbing competition. We were devastated.

for the last time. Her heart suddenly stopped beating. There was no witness, no one to perform CPR, no AED. She was found dead by her uncle the next morning when she didn’t get up as planned to accompany her cousin to a special rock-climbing competition. We were devastated.

Ben Stanton

Ben Stanton Ben’s official cause of death was Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. However that diagnosis remains uncertain and there has been debates among the different cardiologists we have seen as to why Ben’s heart stopped. Ben was seen regularly by Sick Kids and had an appointment in August before starting school that year, which showed no signs for concern. As a family, we have undergone physiologic and genetic testing at Sick Kid’s Hospital and although there was no agreed upon clear and concise diagnosis relating to exactly why Ben died, known genetic markers were identified within our family. As a result, we continue further medical testing and also now regularly carry a portable AED with us. We have ensured that schools, sports clubs, and places of employment are aware of a possible family medical condition and have a protocol in place in the event of a collapse. Since we remain without a clear diagnosis and therefore a clear treatment path, we are aware of how important it is to rely on public response. Since most people who suffer a sudden cardiac arrest don’t know they are at risk for one, we are now trying to be their voice.

Ben’s official cause of death was Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. However that diagnosis remains uncertain and there has been debates among the different cardiologists we have seen as to why Ben’s heart stopped. Ben was seen regularly by Sick Kids and had an appointment in August before starting school that year, which showed no signs for concern. As a family, we have undergone physiologic and genetic testing at Sick Kid’s Hospital and although there was no agreed upon clear and concise diagnosis relating to exactly why Ben died, known genetic markers were identified within our family. As a result, we continue further medical testing and also now regularly carry a portable AED with us. We have ensured that schools, sports clubs, and places of employment are aware of a possible family medical condition and have a protocol in place in the event of a collapse. Since we remain without a clear diagnosis and therefore a clear treatment path, we are aware of how important it is to rely on public response. Since most people who suffer a sudden cardiac arrest don’t know they are at risk for one, we are now trying to be their voice.

Kale Garner

Kale Garner

Matthew

Matthew

Nicholas

Nicholas Today as an individual with a heart arrhythmia and at risk of sudden cardiac arrest, Nicholas balances the joys of life, being active with caution, surrounded by awareness and with an AED in close proximity. Anxiety and emotional stress from his childhood fear of cats and dogs was also overcome through a year-long process of integrating a family dog into his life. There are many activities he can participate in as he gets older and learns to self-advocate and regulate.

Today as an individual with a heart arrhythmia and at risk of sudden cardiac arrest, Nicholas balances the joys of life, being active with caution, surrounded by awareness and with an AED in close proximity. Anxiety and emotional stress from his childhood fear of cats and dogs was also overcome through a year-long process of integrating a family dog into his life. There are many activities he can participate in as he gets older and learns to self-advocate and regulate.